Exhibitions

PERIGEE ARTIST #11 노충현

자리

2016.12.08. THU ~

2017.02.11. SAT

우리가 머무는 곳 - 자리

신승오(페리지갤러리 디렉터)

노충현은 <살풍경>과 <자리>시리즈를 지속적으로 그리고 있으며, 이번 전시에서도 새로운 <자리>시리즈를 선보이고 있다. 그의 전반적인 작업을 이해하기 위해서는 대표적인 연작 중 하나인 <살풍경>을 먼저 살펴보는 것이 필요하다. 그 이후에 이번 전시에서 선보이는 <자리>시리즈가 이전의 작업과 달리 변화된 점과 <살풍경> 시리즈와의 연관성과 차이점들을 비교해 보는 과정 속에서 우리는 자연스럽게 노충현 작업세계에 대해 다가 갈 수 있을 것이다.

처음으로 살펴볼 연작시리즈인 <살풍경>은 한강시민공원을 지속적으로 그려내고 있다. 이는 대부분 한강을 따라 조성되어 있는 공원의 인공적인 시설과 자연의 모습이 같이 드러나는 풍경이다. 공원의 화장실이나 매점, 수영장 등의 다양한 편의 시설들을 보여주고 있지만, 인물들은 거의 등장하지 않거나 익명적으로 나타난다. 그리고 지속적으로 시리즈가 진행되어 가는 동안 밤과 낮의 풍경뿐 만이 아니라 여름의 홍수나 겨울에 눈이 쌓인 풍경들을 통해 특정한 공간이 가지고 있는 시간들의 궤적에 따라 달라지는 결들을 꾸준히 담아내고 있다. 이렇게 <살풍경>은 자연에 인간이 인위적으로 만들어 ....

The Space Where We Stay – Zari

By Shin Seung-oh, Perigee Gallery Director

Constantly involved in serialized works such as Prosaic Landscape and Zari, Choong-Hyun Roh is presenting his new paintings of the Zari series at this art show. In order for one to grasp his oeuvre in its entirety, it is essential to examine Prosaic Landscape. The world of his art can be naturally understood when comparing the similarities and differences between the Prosaic Landscape series, his previous Zari series, and the current paintings on show at this exhibition.

The Prosaic Landscape series consists of portrayals of the Han River civic parks. Its scenes mostly feature artificial facilities amidst natural landscapes, most of which have formed along the Han River. A variety of facilities such as public restrooms, park stores, and swimming pools are often depicted in this series. People, on the other hand, rarely make an appearance in his works and when they do they are anonymous. While working on Prosaic Landscape, Roh has continued to capture the ever-changing scenes of specific spaces with day and night landscapes, floodscapes....

신승오(페리지갤러리 디렉터)

노충현은 <살풍경>과 <자리>시리즈를 지속적으로 그리고 있으며, 이번 전시에서도 새로운 <자리>시리즈를 선보이고 있다. 그의 전반적인 작업을 이해하기 위해서는 대표적인 연작 중 하나인 <살풍경>을 먼저 살펴보는 것이 필요하다. 그 이후에 이번 전시에서 선보이는 <자리>시리즈가 이전의 작업과 달리 변화된 점과 <살풍경> 시리즈와의 연관성과 차이점들을 비교해 보는 과정 속에서 우리는 자연스럽게 노충현 작업세계에 대해 다가 갈 수 있을 것이다.

처음으로 살펴볼 연작시리즈인 <살풍경>은 한강시민공원을 지속적으로 그려내고 있다. 이는 대부분 한강을 따라 조성되어 있는 공원의 인공적인 시설과 자연의 모습이 같이 드러나는 풍경이다. 공원의 화장실이나 매점, 수영장 등의 다양한 편의 시설들을 보여주고 있지만, 인물들은 거의 등장하지 않거나 익명적으로 나타난다. 그리고 지속적으로 시리즈가 진행되어 가는 동안 밤과 낮의 풍경뿐 만이 아니라 여름의 홍수나 겨울에 눈이 쌓인 풍경들을 통해 특정한 공간이 가지고 있는 시간들의 궤적에 따라 달라지는 결들을 꾸준히 담아내고 있다. 이렇게 <살풍경>은 자연에 인간이 인위적으로 만들어 놓은 휴식과 여가의 공간이지만, 작가는 이러한 사람들이 사용하지 않는 시간대의 텅 빈 공원을 그려냄으로써, 독특한 공원의 풍경으로 재현해 낸다. 또한 다양한 시간대와 날씨를 통해 다른 시간과 공간을 그려내고 있지만, 기본적으로 <살풍경>의 한강시민공원의 풍경들은 어두운 밤이나 회색 빛의 뿌연 대기의 표현으로 인하여 차분하고 고요하면서도 한편으로는 쓸쓸하고 차가워 보이는 도시에서 보이는 복잡미묘한 감정들을 불러일으킨다. 이렇게 <살풍경>은 우리가 자주 이용하고 여가를 보내는 공간의 또 다른 면모를 보여줌으로써 작가가 살고 있는 서울이라는 도시 혹은 대한민국의 환경에서 느껴지는 가장 친숙하고 진실된 현실적인 풍경을 반복적으로 그려내는 행위를 통해 공감하고자 한다.

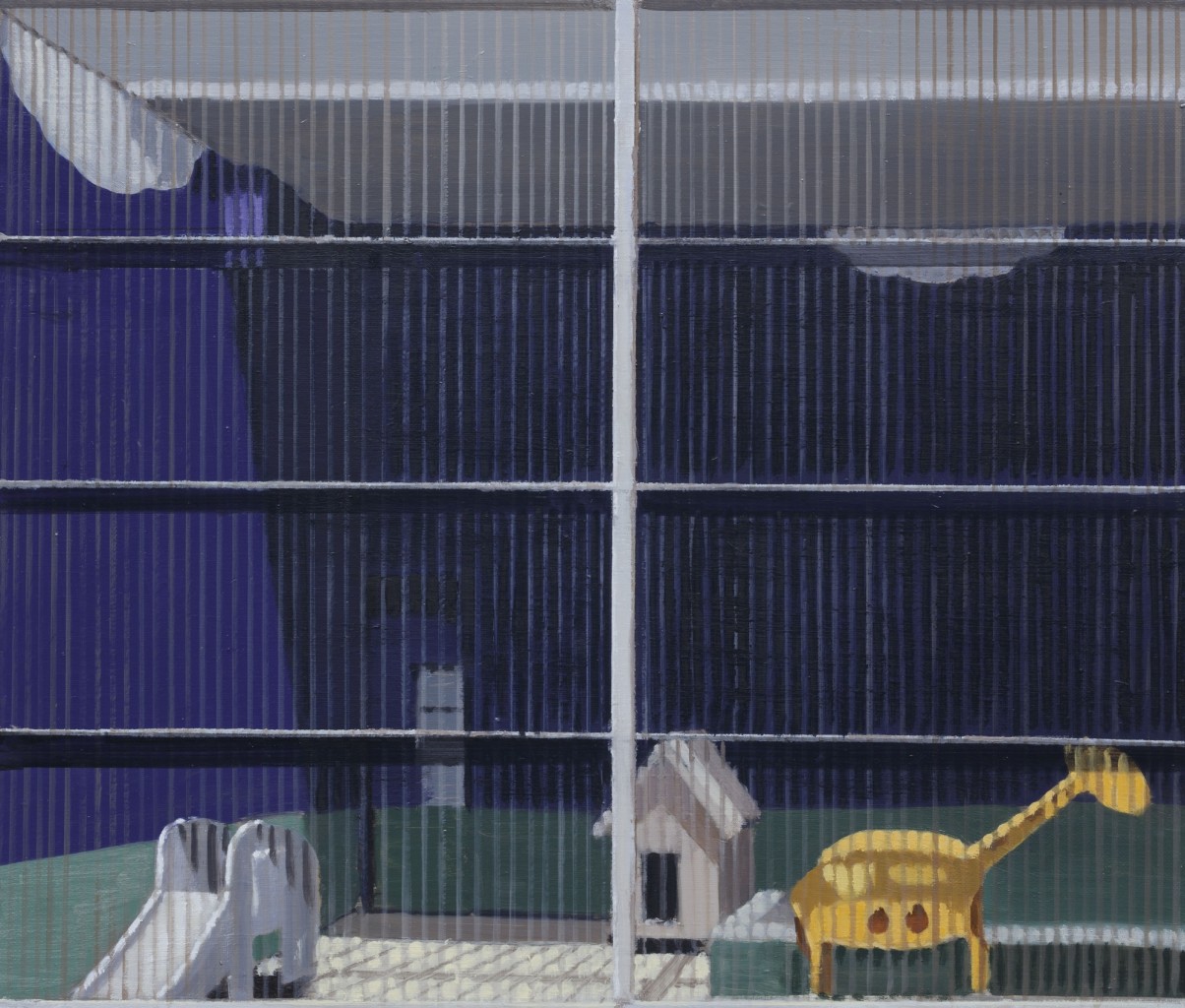

이번에는 <자리>시리즈를 살펴보자. <자리>는 동물원에서 주인공인 동물은 부재한 상태로 남아 있는 공간 만을 그려낸다. 이는 다양한 관점으로 해석이 가능한데, 우리가 주로 동물들을 관찰하고 경험하기 위해 찾아가는 공간인 동물원에 대한 역사적이고 사회적인 관점에서의 장소성에 관한 이야기로 시작되는 것으로 보인다. 그렇지만 작가의 의도는 그 안에서 우리가 집중해서 바라보게 되는 동물이 사라졌을 때 우리의 시선이 넓어지면서 바라보게 되는 공간, 다시 말해 무대 장치에 집중하고 있다. 역사적으로 동물원이라는 공간은 우리가 보기 힘든 다른 토양과 기후에서 살고 있는 동물들을 전시함으로써 제국주의와 근대화 과정을 거치며, 확장된 세력과 여가를 통한 권력의 보이지 않는 힘을 과시하기 위해 만들어 졌다. 이러한 의미들은 시간이 흘러 변화되었지만, 여전히 우리가 즐기는 동물원은 교육과 여가라는 목적으로 감옥과 같은 한정된 공간에 동물을 가두어 둔다는 큰 전제에서 벗어나지 못하는 한계성이 드러나는 공간이다. 이 동물원이라는 무대 안에서 동물들은 사람들에 의해 호기심 어린 눈으로 관람되지만 이 시선은 호기심을 넘어 서 감시의 시선이 숨겨져 있으며, 언제나 관람객이 있던 없던 끊임없이 무대 위에서 감시 당하는 대상으로 전락해 버린다. 그러나 작가가 주목하고 있는 것은 동물들이 아니라 이러한 동물들이 놀 수 있게 만들어 놓은 인위적인 공간 속에 만들어진 장치들이다. 그가 바라보는 동물원이 가지고 있는 이 같은 사실성은 바로 마치 무대 장치처럼 만들어진 우리 속의 공간이며 이는 임의적이고 어설프다. 이 지점에서 작가는 무대장치처럼 보이는 대상을 인식하는 지점들에서 어떤 것을 선택하고 배제하여 어떻게 자신만의 회화로서 만들어 나갈 것인가에 대해 고민하고 있다.

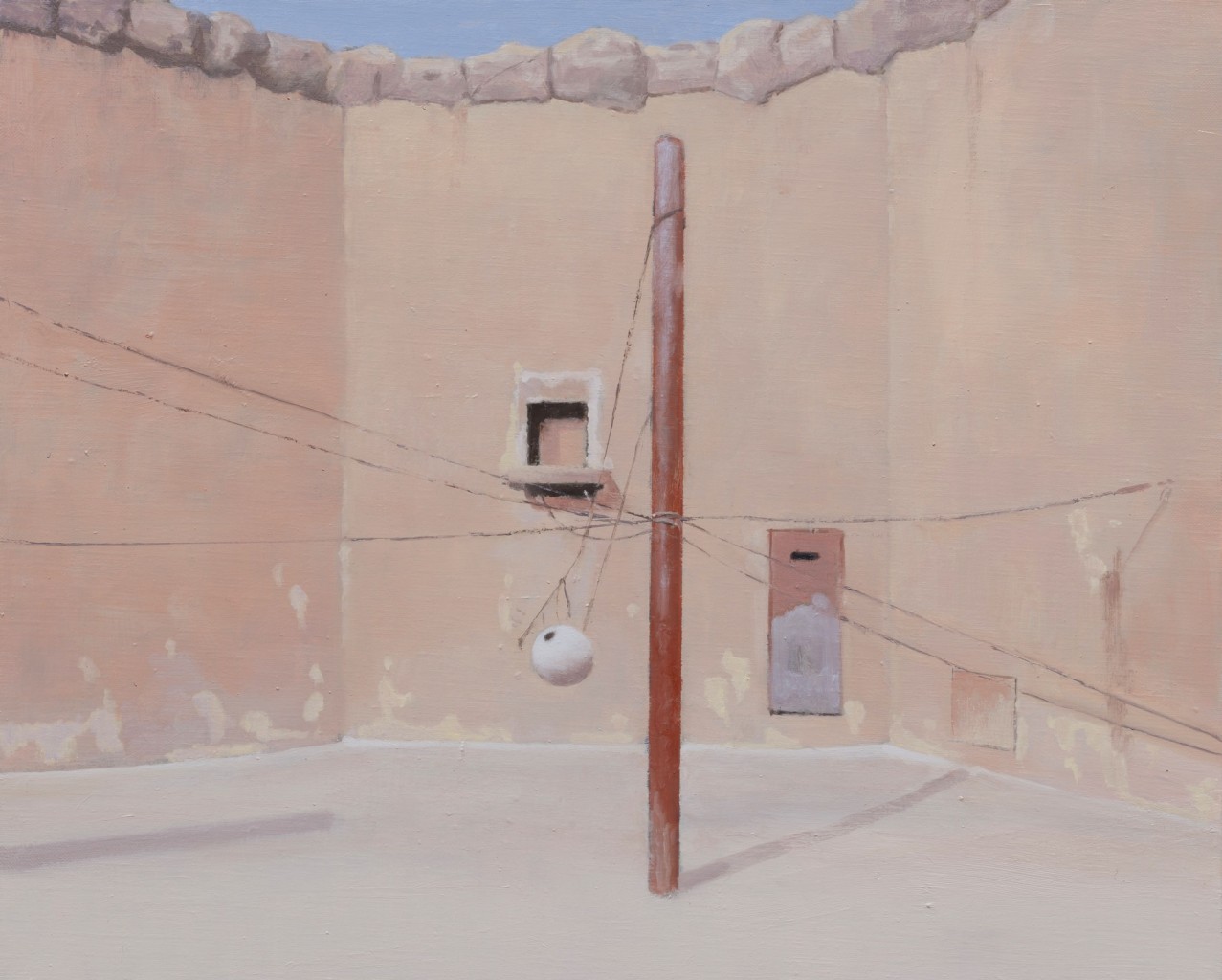

우선은 좀 더 <자리>시리즈를 살펴보자. 작가는 동물원에서 주요한 대상이 되는 동물을 배제한 공간만을 그려냄으로써 동물원에서 동물에게 집중되는 시선을 분산시킨다. 주인공이 사라진 이후에 드러나는 무대는 어설픈 나무기둥들과 밧줄들로 얼기설기 엮어져 있거나 폐타이어로 만든 그네, 인공적인 바위, 숲에 있는 것처럼 보이기 위한 어설프고 엉성한 벽화 등 위태롭고 아슬아슬한 임의적인 공간만이 남는다. 그리고 노충현이 해석해 내는 텅 빈 동물원은 아무런 공기의 흐름도 느껴지지 않는 원래 아무도 살고 있지 않았고, 살수도 없는 진공상태의 밀폐된 공간으로 보인다. 이러한 밀실과도 같은 공간은 오히려 우리가 차분하게 하나하나의 구조를 뜯어 볼 수 있게 만든다. 그리고 우리의 시선이 머무는 곳마다 <살풍경>과는 달리 움직임이 전혀 없는 정적만이 흐르는 공간으로 나타난다. 결국 작가에게 있어서 이 동물원의 무대장치는 우리가 살고 있는 이 세상의 위태롭고 아슬아슬한 구조와 다르지 않음을 보여준다.

그렇다면 이번 작업이 이전의 <자리>시리즈와는 어떤 변화된 점을 찾아볼 수 있을까? 작가의 시리즈 작업은 결국 내용적인 부분은 큰 변화가 없다. 변화가 있다면 시간이 흘러가면서 점점 더 작가의 내면에 쌓여가는 인식과 사유일 것이다. 굳이 언급하자면 공간을 표현하는 방식에서 미세한 변화가 보인다. 동물원이라는 한정된 공간의 밀폐성과 답답함의 공기를 담아내면서도 작가가 원하는 데로 리얼리티의 구조를 드러내기 위해서 작가 자신의 감정선의 표현을 절제하는 모습이 보인다. 이번 <자리> 시리즈에서는 이전 보다 더욱 한정된 공간과 무대장치에서 답답함과 닫혀있는 공간이 가지고 있는 무색 무취의 고요한 정적으로 인해 심리적인 압박감이 더욱 느껴진다. 이는 이전의 시리즈와는 다르게 작가가 무대장치를 둘러 싸고 있는 경계의 역할을 하는 동물원의 낡고 거친 무채색 계열의 실제로는 낡고 지저분한 벽들을 표현하는 데 있어서, 감정의 쏠림에 의해 거친 붓질로 표현하기 보다는 부드럽고 얇은 색 면으로 표면을 처리하고 있기 때문이다. 이렇게 절제된 표현은 오히려 우리에게 <살풍경>의 풍경이 가지고 있는 쓸쓸하고 덩그러니 남아 있는 외부의 공간에서 느껴지는 촉각적인 감성과는 다르게 우리가 쉽게 바라보지 못하고 경험하지 못하는 공간, 시간성은 완전히 배제된 공감각적인 공간으로 나타난다. 이러한 동물원의 벽들은 그 대상이 되는 무대장치와 대조적으로 마치 우리의 심연을 돌아보게 만드는 조밀하면서도 내밀한 시선으로 공간을 바라보게 만들고 있다. 이렇듯 <살풍경>이 자연과 인공적인 것이 뒤섞인 공원에 들어가 직접적으로 우리가 그 공간을 점유하면서 시간을 보낼 수 있는 열린 공간이라면, <자리>가 다루는 동물원은 이와는 거리를 두고 바라볼 수 밖에 없는 대조적인 닫힌 공간을 다루고 있다. 이렇게 반대되는 공간을 다루기는 하지만 <살풍경>은 외부와 표면과 시간성에 집중 한다면, <자리>는 작가 내면의 심연을 드러내는 데에 집중하고 있어 서로의 시리즈를 보완해주는 관계로 보인다.

지금까지 살펴본 노충현의 연작 작업들은 지금 우리가 살고 있는 현실의 리얼리티를 과장되지 않게 솔직하게 담아내고 있다. 그에게 있어서 그린다고 하는 행위는 결국 사실성이 가지고 있는 표면 이면에 숨겨져 있는 의미들을 작업에서 어떻게 하면 자연스럽게 드러나게 할 수 있을까에 대한 고민들의 연속으로 보여진다. 따라서 그의 연작 시리즈들은 작업이 진행되어 갈수록 이러한 작가의 시간성이 쌓여가면서 자연스럽게 그 의미들의 구조를 드러내는 작업이 되어 간다. 그리고 이런 점이 노충현이 지속적으로 이 두 연작시리즈를 순차적으로 선보이는 이유이다. 여기서 다시 노충현은 어떤 회화를 만들어 나가고 싶은지 대한 고민으로 돌아와보자. 우리가 노충현의 작업 세계 전반에서 발견 할 수 있는 것은 작가 자신의 인식과 사유의 결과물들인 작품 안에서 소재라는 대상에서 나오는 사실성과 함께 균형을 유지하기 위해 노력하는 태도이다. 지금까지 살펴 본대로 작가는 주체적인 관점과 리얼리티 사이에서 나타나는 공간을 그려내기 위해서 반복적으로 그림을 그려낸다. 그의 회화는 원본이 분명히 존재하며, 자신의 눈으로 관찰한 실제의 공간, 그리고 그것을 사진으로 기록해 낸 이미지들을 바탕으로 하고 있다. 이는 작가가 자신이 살고 있는 서울이라는 주변 환경, 넓게는 대한민국에서 드러나는 무형의 이미지들을 담아내는데 진력하고 있기 때문이다. 물론 그의 작업을 보면 쓸쓸함, 황량함 등의 단어가 떠오르는 것이 사실이다. 하지만 이러한 것들은 우리들에게 우리가 살고 있는 세상에 대한 부정적인 부분을 전달하기 위한 의도를 가지고 있는 것은 아니다. 단지 작가 자신에게 체득되어 있는, 삶에 맞닿아 있는 공간들이 가지고 있는 구조를 온전히 자연스럽게 드러내기 위함이다. 그리고 작가의 작품은 그가 할 수 있는 가장 단순한 회화의 방식으로 재현해 내는 풍경과 공간들을 통해 관객들이 스스로의 눈으로 인식하게 만들기 위한 수단일 뿐이다. 이것이 연작으로 그려내는 공간들이 노충현만의 회화로 귀결되는 방식이다. 결국 노충현은 자신의 작업을 통해 우리가 우리 주변에서 느끼는 것들을 자신의 내면에서 스스로 새롭게 생각해내는 것들을 정확하게 표현할 수 있기를 바라고 있다. 또한 내가 바라보는 사물을 사물 그 자체로 이해하고, 이를 통해 리얼리티의 구조를 자신만의 틀에 담아낼 수 있다면, 그것이 바로 우리가 사는 인생이라는 삶의 자리를 이해할 수 있는 방법이라고 말하고 있다.

By Shin Seung-oh, Perigee Gallery Director

Constantly involved in serialized works such as Prosaic Landscape and Zari, Choong-Hyun Roh is presenting his new paintings of the Zari series at this art show. In order for one to grasp his oeuvre in its entirety, it is essential to examine Prosaic Landscape. The world of his art can be naturally understood when comparing the similarities and differences between the Prosaic Landscape series, his previous Zari series, and the current paintings on show at this exhibition.

The Prosaic Landscape series consists of portrayals of the Han River civic parks. Its scenes mostly feature artificial facilities amidst natural landscapes, most of which have formed along the Han River. A variety of facilities such as public restrooms, park stores, and swimming pools are often depicted in this series. People, on the other hand, rarely make an appearance in his works and when they do they are anonymous. While working on Prosaic Landscape, Roh has continued to capture the ever-changing scenes of specific spaces with day and night landscapes, floodscapes in summer, and snowscapes in winter. While the series features spaces created by people for relaxation and leisure, Roh focuses on representing the distinctive landscapes of empty parks devoid of human life. Scenes of parks in different time zones and under the influence of different types of weather are portrayed, arousing mixed feelings in viewers as they observe the hushed and placid yet desolate and cold hearted atmospheres through a depiction of a dark night or the cloudy gray air. Roh manages to unveil a new aspect of a space we often visit to pass the time, thereby arousing our feelings of affinity toward the city of Seoul and the Korean landscape we inhabit through his repeated portrayals of immensely familiar and realistic scenes.

Similarly, the Zari series features zoo locations devoid of animals, its main component. Open to a range of interpretations, this series starts from stories apropos of the placeness of the zoo, a space we usually visit to observe and experience animals, as seen from historical and social perspectives. All the same, Roh concentrates on the scene that is visible when animals pass away in the zoo, that is, stage setting. Historically, zoos were formed to flaunt the invisible influence and strength of imperialist powers by exhibiting animals that normally live in different climates and terrains. The purpose of zoos has changed over time but this place which gives us such happiness is still one in which animals are confined to limited areas like prisoners for the sake of our own education and entertainment. With the zoo as a stage, animals are observed with curious eyes which mask surveillance. Zoo animals have degenerated into objects of surveillance on a stage regardless of whether spectators are there or not. However, in this series what the artist emphasizes is not the animals but the equipment set in an artificial space in which the animals play. This reality of the zoo he depicts is a cage resembling a stage set, something which appears somewhat arbitrary and imperfect. In this respect, the artist seriously considers the ways in which he can forge his own art, determining what he selects and excludes.

His portrayal of spaces devoid of animals distracts us in a way that causes our eyes to search for them in his works. Left behind after the main characters disappear is an arbitrary and precarious space characterized by awkward looking tree trunks, a swing made of entangled ropes and waste tires, artificial rocks, and poor, shabby murals of groves. And, an empty zoo Roh interprets seems to be a sealed space in which no flow of air is sensed and nobody can live. This secret room-like space rather enables us to scrutinize each structure one by one. Unlike in the Prosaic Landscape series, each space has a hushed atmosphere where no movement is sensed. After all, the artist shows that the stage set of this zoo is no different from the precarious structure of this world.

If so, what’s the difference between this work and the previous Zari series? In terms of content there is not much change in his series. If some, that may be change in his perception and thought. That being said, his way of depicting space has slightly changed over time. Roh seems to restrain his emotional renditions in order to unveil the structure of reality as he pleases while bringing forth the closeness and stuffiness deriving from a zoo’s confined space.

Some pressure is more apparently sensed in this series due to the stuffiness, stillness, and quietude in a closed space. He treats the surfaces of the zoo’s old, dirty walls that work as the borders with the fields of mild, thin colors rather than depicting them in rough brushstrokes influenced by his emotion. Through this moderation of expression he represents the space we have never viewed or experienced and a synesthetic space in which temporality is completely excluded, unlike any tactile emotion sensed in an external space in loneliness and aloofness the Prosaic Landscape series incarnates. These walls, by contrast with the stage setting, make viewers scrutinize the space with clandestine eyes. The Prosaic Landscape series deals with an open space with the artificial mixed with the natural we can enter and occupy in person whereas the zoo the Zari series captures is a closed space we just look at from a distance. Although the two series address opposite spaces in this way, they seem to be complementary to each other as the former focuses primarily on the external surface and temporality while the latter concentrates on unveiling the artist’s inner world.

Roh’s serialized works reviewed above are candid representations of realities of the world we currently inhabit. To the artist, an act of painting seems to be an expression of his concerns about how to naturally unmask meanings hidden behind realities. Accordingly, his series naturally discloses the structure of such connotations when temporality is accumulated over time. That’s why Roh has presented the two serialized pieces in order. We may come back to his concerns about what painting he’d like to create. What we can discover in his oeuvre is his attitude to maintain the balance of his perception and thought represented in his work and subject matter and the reality found in his pieces.

As examined so far, Roh has repetitively produced paintings to portray spaces between his subjective perspective and reality. His paintings obviously have their referents, anchored in the images of real spaces he observed with his own eyes and documented in photographs. He has occupied himself with capturing intangible images found in his surroundings of Seoul where he lives and works and broadly in Korea. In fact, his work brings some words like forlornness and desolation to mind. However, these are not intended to convey some negative aspects of the world we inhabit. They are rather intended to naturally or wholly reveal the structure of space the artist has internalized and his life has contacted. His work is nothing but a means to have viewers perceive the scenes and spaces he has represented in his own painterly manner as simple as he could with their own eyes. This is the way the scenes and spaces in his series can be realized as paintings only Roh is able to forge. After all, he wants to accurately portray what he newly conceives through what we feel in our surroundings. He also tries to grasp a thing through the thing itself and to hold the structure of reality in his own distinctive receptacles. He seems to allude that this is a way to comprehend the space of our life.